Our Mission & Vision

Little Free Library is a nonprofit organization based in St. Paul, Minnesota. Our mission is to be a catalyst for building community, inspiring readers, and expanding book access for all through a global network of volunteer-led Little Free Library book-exchange boxes.

Our vision is a Little Free Library in every community and a book for every reader. We believe all people are empowered when the opportunity to discover a personally relevant book to read is not limited by time, space, or privilege.

Little Free Library World Map

Little Free Library (Wiki)

Source: The Philadelphia Citizen

How to Start Little Free Libraries in Your Neighborhood

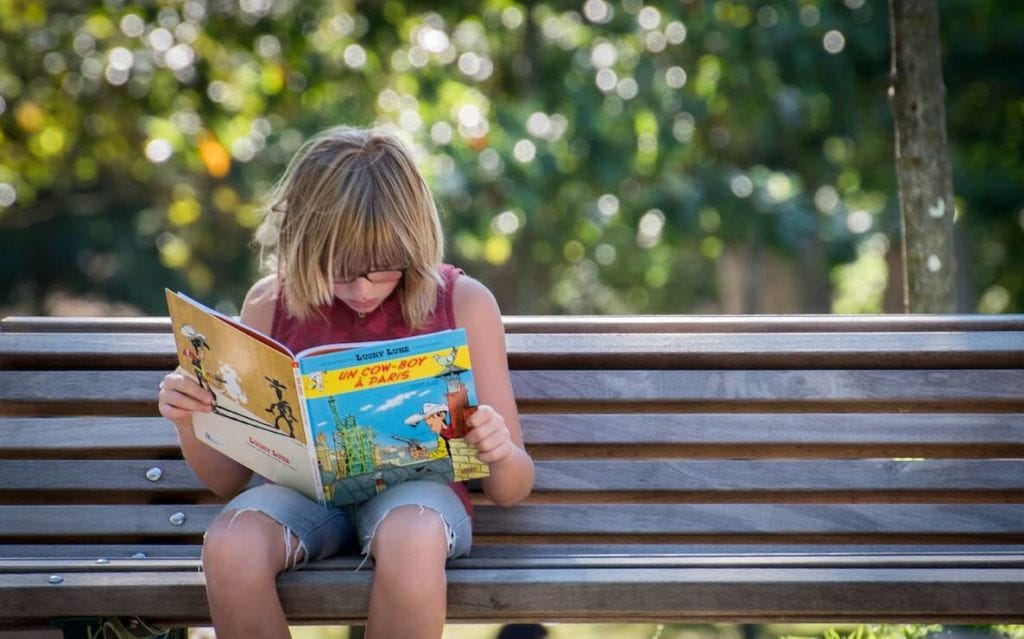

After a year of majority-online activities, here’s how you can encourage someone to crack open a book by building a little free library

May. 10, 2021

After a year of majority-online school, work and activities, picking up a physical book may seem like a thing of the past. But reading is also, of course, a much-needed escape, a way to travel if only through our imagination. At least, that’s one of the goals Darlene Burton is keeping in mind as she prepares to install a new, little free library, in front of her house in Philadelphia’s Harrowgate neighborhood.

“I want kids to go on adventures by reading books,” says Burton, who will be installing a library filled with children’s books.

Little free libraries are small, often wooden boxes that look similar to bird houses—but larger—and are packed with books. Started by the late Todd Bol, who created the Little Free Library Movement, these libraries operate with a “take a book, leave a book” model, and have been popping up in neighborhoods throughout Philly and across the United States.

As their name implies, the libraries are little and free for public use. And with just a few tools and tips, anyone can make one. Here are some steps to get started:

Supplies needed for little free libraries

Wood

Saw (jigsaw is recommended)

Drill (automatic is recommended)

Shovel

Paint

Permit (depending on placement)

Books

Readers

How to build little free libraries in nine steps

1. Find an interested neighborhood or group

Before starting a little free library, you’ll want to think about where it will go and who it will benefit. Consider neighborhoods that are not within walking distance from a Free Library of Philadelphia, and ask people for permission, or feedback, on placement.

If you do not live in the neighborhood where you’ll be building the library, make sure it benefits, not burdens, the community. Talk to community members first, and have a plan for how you will maintain the library.

A little free library building session took place at Harrowgate Park on a recent Saturday—as part of an initiative called the Trust Project, a collaboration between Friends of Harrowgate Park, Creative Resilience Collective (CRC), and Mural Arts.

The organizations consulted community members before the build, which was essential to maintaining trust in the neighborhood, says Marissa Rumpf, president of Friends of Harrowgate Park.

“The little libraries were an idea that came not from Mural Arts or from CRC, but from the neighbors ourselves,” adds Rumpf. “We thought about what the kids and the neighbors in our community really need, and we kept coming back to the idea of access to books and literature, and literacy, which goes along with other programming that park neighbors have initiated.”

2. Assemble a group

Because the library will be for public use, you may want to have a group of people involved in building it and setting it up. Consider holding a little free library building session at your local park or in your own yard.

3. Look up design ideas

Little Free Library is a national brand at this point, and the organization offers design inspo and other set-up tips on their website. You can also buy their book, “Little Free Libraries & Tiny Sheds: 12 Miniature Structures You Can Build,” which details how to put different design options together.

4. Gather your tools, and get to work

You don’t need a full woodshop to build a little free library, but you’ll want a few basic tools to start out.

Carly Najera teaches art and tech ed at Bensalem High School—including woodshop—and led the recent workshop at Harrowgate Park. “You can always cut things by hand,” Najera says. “It just takes a long time. Do you have the patience to sit there and cut things with just a regular saw?”

If not, you’ll be more efficient with a jigsaw, she says. And if you don’t have tools on hand, you can rent some for a day from one of Philly’s tool libraries, like Tacony Tool Library and West Philly Tool Library for a small fee. (West Philly Tool Library asks people to pay a sliding scale membership between $20 and $50 a year, based on income.)

Side note: Not so different from free little libraries, tool libraries are places where members can rent a tool for a project, without committing to a full purchase. Unlike little free libraries, where you “take a book, leave a book,” however, if you rent a specific tool, you have to give that same tool back.

5. Start decorating!

Najera says painting libraries is a way more popular activity than constructing them. Paint and decor aren’t necessary for the functionality of your library, but are nonetheless a way to personalize your library to make it special to yourself and the community it serves. So get creative!

Consider adding features like a community bulletin board to the exterior of the library, or painting it with meaningful words or phrases that represent your community.

6. Get permission—or a city permit—before you install

If you are placing your little free library on city property, like a park, you will need to get a zoning permit first. You can apply for a permit, here.

If that sounds like too much work, consider placing the library on private property—like your or a neighbor’s front yard. (If placing a library in a neighbor’s yard, they’ll need to give you the “OK,” first, obviously.) In Harrowgate, Burton offered to set up her library—which is part of the Trust Project—in her yard not only to avoid the permit process, but to help her community.

“I always try to promote literacy in the community,” Burton says. “I believe the more knowledge you have, the better off you are in life, because we all know knowledge is power.”

7. Install

If your library is outside, install it into the ground securely. Little Free Library’s website has tips for how to do this with a wooden post. You can use this method for installing your library into a planter, as well.

If your library is inside, you do not need to install it into the ground.

8. Host a book drive, donate books

Once the library is in place, it’s time to fill it with books! Ask your neighbors if they have old—or new!—books that they are willing to donate, and look through your own shelves as well.

After you’ve gathered an initial set of books, the hope is that the supply will grow and change over time.

“The idea is: Take a book, give a book, when you’re done you put it back, find something else,” Najera says. “I always feel like people have extra books lying around. I know I do.”

In Harrowgate, they will be filling the libraries with a selection of English and Spanish books, to cater to the neighborhood’s Spanish-speaking population.

9. Spread the word, and start reading!

Once the library is built, decorated, installed, and stuffed with books, it’s time to start using it! Remind your neighbors that it exists, and take advantage of it yourself. You can also up your community engagement efforts by reading books with others, and helping your younger neighbors learn to read.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece omitted the name of Todd Bol, who launched the movement, and misspelled Marissa Rumpf’s last name.

Source: American Libraries Magazine

The Question of Little Free Libraries

Are they a boon or bane to communities?

By Megan Cottrell | January 2, 2018

They have been popping up in droves. On front lawns and street corners. In parks, community centers, and hospitals. You can even find them at beaches, malls, and barbershops. What started in 2009 with a box on one man’s lawn has spawned 60,000 Little Free Libraries around the globe. The ubiquitous book-exchange boxes now outnumber public library branches in the US about three to one.

But are these seemingly wholesome book boxes helping or hurting staffed libraries? And how are librarians and communities across the country leveraging the presence of these outposts?

Little Free Library Capital of the World

When Pam Weinstein first noticed the school bus parked outside her home in Detroit’s Rosedale Park neighborhood and her lawn crowded with children, she thought there was some mistake. “Did the bus stop get moved?” she wondered.

But the kids were gathered around a wooden box planted in Weinstein’s front yard—a Little Free Library—while the bus driver helped each child pick out a title to take home. It was a ritual they repeated every Friday for almost year.

“They could clean it out in one visit, so I started putting more children’s books in there,” says Weinstein, whose book-exchange box was installed as part of a project to plant 313 of them around the city, effectively making Detroit the Little Free Library capital of the world.

Despite numerous articles and press releases announcing its renaissance and rebirth, Detroit is still a city that struggles with poverty, with more than 35% of its residents living below the poverty line in 2016. A recent New York University Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development study showed that in many parts of the Detroit area, books are scarce. In Hamtramck, a small city bordering Detroit, for example, there is as few as one book for every 42 children.

As a reporter for the Detroit News for 25 years, Kim Kozlowski has seen the city through some difficult times, including when FBI homicide statistics prompted media outlets to crown it as the “murder capital of the US” in 2014. That same year, she noticed a Little Free Library pop up in her own suburban neighborhood and how it created community connections among residents there.

“The city had just climbed out of bankruptcy, and there was this sense of hope and excitement. People were banding together to do what they could to raise the city up. I thought I would start raising money to buy these Little Free Libraries, and it grew from there,” says Kozlowski, who would go on to head the nonprofit Detroit Little Libraries campaign.

Three years later, Kozlowski estimates there are about 500 Little Free Libraries in the city, including 97 that have been placed in front of Detroit public schools. Recently, Detroit Little Libraries and the national Little Free Library nonprofit announced a new initiative to put a Little Free Library in front of every police precinct in Detroit.

Media coverage of Detroit Little Libraries has been positive, with reports that they encourage literacy and replenish “book deserts.” But a study released last year questions that assumption. Jane Schmidt, librarian at Ryerson University in Toronto, noticed these fawning claims and was skeptical.

“They were using these warm and fuzzy words like ‘community building’ to describe these little boxes, while most of the media coverage about actual libraries is saying, ‘Who needs libraries anymore? Is the public library still relevant?’” says Schmidt.

So Schmidt joined with human geographer and librarian Jordan Hale of the University of Toronto to study Little Free Libraries, including mapping Toronto’s book boxes in relation to public library branch locations. The geographical analysis of Toronto’s Little Free Libraries confirmed their suspicions: the city’s book-exchange boxes didn’t water so-called “book deserts” but instead existed in affluent areas with easy access to public library branches.

Schmidt says no one denies these tiny book repositories are adorable, but what they actually do for literacy is unclear.

“It’s a lovely concept, it really is,” says Schmidt. “But when we think about the people who are fawning over them, are they people who are actually relying on the public library for their information needs?”

She adds, “Public libraries are serious business and lifelines for a lot of underserved communities.”

Harnessing the phenomenon

Detroit’s Little Free Libraries are standalone entities run by individual volunteers, but many public libraries across the US have gotten into the Little Free Library business themselves.

Friends of the Bismarck (N.Dak.) Public Library secured funding to purchase 13 Little Free Libraries to spread throughout the city. Instead of waiting for residents to install their own, the library took applications from patrons who wanted to be caretakers and chose them based on location to ensure the book exchanges would blanket the area.

BPL Director Christine Kujawa says community caretakers were allowed to personalize their libraries; some simply stained the wood box, while others painted them with intricate designs. Overall, she says, the project has been incredibly successful.

“Citizens continually ask us if the Friends of the Bismarck Public Library will do this again, and if so, can they put their name in now so they’re on the list of applicants,” says Kujawa. “People are starting to create their own Little Free Libraries from repurposed material, such as used newspaper racks.”

Kujawa says she sees Little Free Libraries as a way to complement and expand existing library offerings, such as the library’s bookmobile, which services the largely rural Burleigh County where Bismarck is located. Kujawa says the library has chosen six more spots to install Little Free Libraries in the area.

“This will allow rural citizens to have free access to reading material in between the bookmobile visits,” says Kujawa.

Salina (Kans.) Public Library embarked on a similar endeavor, building nine Little Free Libraries for the city’s nearly 50,000 residents. The public library built the boxes with money from a large donation bequeathed by a patron who passed away suddenly and thought it was a great way to honor his memory. One box that was made to resemble a rocket—cylindrical with a pointy top, the clear glass hatch door providing access to a shelf full of books—was placed in a park named after one of Salina’s most famous residents, former NASA astronaut Steve Hawley.

Lori Berezovsky, community engagement coordinator for Salina Public Library, says soon after the book exchanges were built, stocking and checking on them became a lot of work. The library put out some ads asking for residents to adopt a Little Free Library and care for it for a year, and decided to give volunteers access to donations and discarded library books to keep them stocked.

“It’s increased the number of volunteers and given them some ownership,” says Berezovsky. “I’ve realized the neighbors are paying attention and keeping an eye on them, too.”

For some folks, says Berezovsky, Little Free Libraries have become a family bonding activity. She says a dad and his daughter who has developmental disabilities ride their bikes to a certain Little Free Library once a week; they find a book to borrow and bring along one to contribute. There is also a mother–daughter duo who scours garage sales for books to donate. When they noticed that children’s books disappear particularly quickly, they began focusing on finding more.

“Kids who can’t drive, they don’t have a means to get to the library unless an adult brings them,” says Berezovsky. “If they can get some books that are of interest to them, that’s a great thing.”

Complement or competitor?

Back in 2009, Todd Bol built a little wooden schoolhouse, filled it with books and installed it on his front lawn as a tribute to his late mother. Today, Bol is the founder and executive director of the nonprofit Little Free Library. He says there are more than 60,000 Little Free Libraries registered worldwide—up from 50,000 last year—with 90% of them located in the United States.

One criticism researchers Hale and Schmidt, among others, have of Little Free Library is the nonprofit’s charge to use the Little Free Library name. The nonprofit charges $39 to register and use the name, and a few hundred bucks for the average prebuilt book-exchange box. Hale and Schmidt have questioned the need for a registration fee and branded name.

“You get a charter number. They put you on a map. You get some pamphlets and a sticker. Why does that come at such a substantial cost?” says Hale. “It could be very free and very grassroots and lovely.”

“Where is the money going? Is it going to literacy?” asks Hale. “The website says they build hundreds of installations in underserved communities, but where are those exactly, and were they funded by donations or charter fees?”

Bol says he appreciates the constructive criticism from Hale and Schmidt and hopes their questions can spur the nonprofit to refine its mission.

“We’re trying to do a better job of making transparent the work we do behind the scenes to fulfill that mission and to increase book access,” says Bol, who points to its Impact Library Program, which aims to provide 50 book exchanges to underserved communities this year.

“We are sometimes perceived to be a big institution, but we’re actually a small nonprofit—just 12 people in a Wisconsin office. We’re not ‘big’ Little Free Library,” says Bol.

And, he says, more than 600 public libraries around the country use Little Free Libraries as an extension of their services.

“Little libraries obviously cannot provide the depth and breadth of services that public libraries provide,” says Bol. “They can, however, act as natural complements to the public library, providing easy access to books to residents of neighborhoods or small towns that are far away from public library resources.”

But Hale and Schmidt point to at least one place where Little Free Libraries are seen as a substitute for true public library services. When budget cuts caused the El Paso (Tex.) Public Library to implement a $50 annual fee for nonresidents to use the library system, the tiny town of nearby Vinton came up with a plan: five Little Free Libraries spread around the community. The town would build them, and keeping them stocked with books would be up to the people of Vinton themselves.

When Detroit Public Library (DPL) closed its Gabriel Richard branch in 2011, 4th graders at a local elementary school installed a colorful painted bookcase and a sign reading “Outdoor Library” in front of the shuttered building. It was one of four libraries to close that year—two have since reopened, though only two to three days a week.

Despite budget shortfalls that led to reduced hours or staff cutbacks at other branches, DPL was recently able to restore Sunday hours at its main library, which hasn’t been possible since 1981, and it has brought back Sunday hours to two of its branches.

Although Little Free Libraries can provide access to books when hours are reduced or branches aren’t nearby, the quality of the books inside is often poor, says Mary-Catherine Harrison, professor of English at University of Detroit Mercy, who runs the nonprofit Rx for Reading Detroit.

“Often with Little Free Libraries, you get a lot of books people just want to get rid of. They’re not books that are adding value,” says Harrison. “That’s a real difference from libraries—you have children’s librarians who are acting as that resource, recommending books, making displays of books, choosing the best books.”

Harrison’s nonprofit also focuses on expanding access to print materials for Detroit kids, but in a different way. Rx for Reading creates caches of children’s books inside Detroit’s community centers and institutions, like WIC clinics, legal aid offices, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. When families use these existing resources, kids get to take a book to keep. Rx for Reading both fundraises to buy books and takes donations, although Harrison says they’re thoughtful about which books they give away, and they refurbish books to make sure they don’t look like somebody’s castoffs.

Harrison says she does support the Little Free Library effort and that public libraries have their own barriers when it comes to low-income residents accessing resources. In the DPL system, she says, approximately 56,000 patrons—about 14%—are blocked from borrowing materials and using public computers because they have incurred more than $10 in fines. Harrison says she’d like to see more amnesty policies at public libraries across the US to allow broader access to services.

At least a few DPL librarians are taking advantage of Little Free Library locations to further their mission. Barbara Parker-Hawkins, manager and children’s librarian at DPL’s Chaney branch, keeps a box of books in her storeroom to give to kids to keep in situations where they can’t borrow books.

“When I run into a situation where the child might not be in a stable home environment, I tend to just give them a book so they have something to read,” she says.

Parker-Hawkins sees Little Free Libraries as an extension of that box in her storeroom. When it came time to weed through Chaney’s children’s collection and make room for new books, she boxed up her favorite titles and called Weinstein, the steward of the neighborhood’s Little Free Library.

Despite budget cuts and branch closings in recent years, Parker-Hawkins doesn’t feel any animosity toward these ubiquitous book boxes, even though they don’t offer the multitude of services real libraries provide.

“I think anything where you have a book is a library. The more we have out there, the better,” she says. “I don’t think we’re going to put the library out of business by any means. I see them as helping out the libraries. I’m very glad they’ve come along.”

Outposts in Other Cities

Public libraries across the US are integrating Little Free Libraries in interesting ways. Here are a few examples.

Little Free Library treasure hunt. Northbrook (Ill.) Public Library made its two Little Free Libraries part of its summer reading challenge. Both child and adult patrons could visit a book-exchange box and find a token that would enter them into a drawing for prizes.

Barbershop book exchanges. Houston Public Library installed 50 Little Free Libraries in front of barbershops in low-income areas of the city as part of its Groomed for Literacy program. Adults enrolled in the county’s workforce development classes decorated the book-exchange boxes, with some even featuring tiny red-and-white barbershop poles.

Beach reads. Long Beach (N.Y.) Public Library has installed four Little Free Libraries along the city’s beach boardwalk, encouraging beachgoers to pick something to peruse while they enjoy the sand and surf.

Update: Corrected to indicate that Kim Kozlowski does not report for the Detroit Free Press, January, 1, 2018.

Ways to connect

Telegram: @JoelWalbert

Email: thetruthaddict@tutanota.com

The Truth Addict Telegram channel

Hard Truth Soldier chat on Telegram

Mastodon: @thetruthaddict@noagendasocial.com

Session: 05e7fa1d9e7dcae8512eed0702531272de14a7f1e392591432551a336feb48357c

Odysee: TruthAddict

Donations (#Value4Value)

Buy Me a Coffee (One time donations as low as $1)

Bitcoin:

bc1qe8enf89g667dy890j2lnt637xqlt9wvc9f07un (on chain)

bc1qnqjdudgc0qr5yfrp826nxes8kljf9p07mwt3q3yjrd6gqwj0lqtswmy39s (lightning)

nemesis@getalby.com

joelw@fountain.fm

+wildviolet72C (PayNym)

Monero:

43E8i7Pzv1APDJJPEuNnQAV914RqzbNae15UKKurntVhbeTznmXr1P3GYzK9mMDnVR8C1fd8VRbzEf1iYuL3La3q7pcNmeN

Share this post